The controversial Silicon Valley-funded quest to educate the world’s poorest kids

A Bridge Academy teacher reads from her tablet as students recite a classroom exercise at the Kingston location in Nairobi, Kenya.

On a Monday morning in October, Faith stands before her class of kids, ages 10 and up. She looks down at her tablet computer, which details the day’s lessons. Her teaching plan gives instructions down to the minute, including when kids should stand up, solve problems, cheer for a classmate, and work with others.

They have precisely two minutes to discuss a prompt—What is your favorite thing to wear?—with their desk mates. Then they have 38 minutes to write one page on a similar question. Faith reads the directions from the tablet, scans the classroom, and “signals,” or snaps her fingers, when it is the students’ turn to respond.

As the students write, the teacher makes her way around the classroom, peering over their shoulders. This is a strategy called “check, respond, leave.” She instructs one student not to cross out his words, and to make sure he indents. She does not appear to read what he has written, or correct misspelled words.

She calls on one student to read his answer. He reads, haltingly but confidently, that he likes to wear blue jeans “because they make me look like a big man.” The students laugh. Faith smiles and responds: “That is correct.” She calls on another student. His answer, too, is “correct.”

Reaching the end of the lesson, she doesn’t ask if there are any questions. “Today our goal was …” she pauses, looking at the blackboard where she wrote the lesson goal, “to practice writing.”

It might sound as if Faith is teaching in a high-tech classroom in Silicon Valley. In fact, she’s in Mukuru, one of Nairobi’s biggest slums. She works for Bridge International Academies, a Valley-backed chain of schools in Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Uganda, and India.

Founded by Shannon May and Jay Kimmelman in 2007, Bridge aims to bring affordable, high-quality private school education to some of the poorest students in the world. The company addresses a grim reality in many developing countries: nearly 600 million kids in the world are either out of school, or in school but not learning. In many countries, teachers lack proper training and materials. Worse, many teachers often don’t show up. According to the World Bank, during random spot-checks across seven African countries, 20% of teachers were absent, and another 20% were in the school but not in the classroom.

Bridge’s solution to the problem is well-suited to these tech-enabled times: Optimize education by standardizing and automating some of it. Every week, teachers at Bridge’s 599 schools download highly-scripted lesson plans designed by experts in Cambridge, Massachusetts, along with in-country teams. During the day, in any given country, teachers in the same grade are delivering the same lesson. Bridge collects data that allows it to compare the efficiency of teachers in one school to another, or measure the performance of students across different classes, schools, and countries.

The results are promising. Teachers show up; kids have learning materials; teachers get detailed lesson plans and plenty of feedback; and data-based evidence informs class design.

“There are hundreds of millions of kids not in school and hundreds of millions in schools and not learning. Bridge exists to close that gap and to show its possible to run high-performing schools on a constricted budget,” says May.

Not everyone is dazzled by Bridge’s approach or results, however. And it’s become something of a lightening rod for controversy over issues as varied as whether trying to make a profit from teaching the world’s most marginalized children is ethically fraught, to intense debate over its teaching methods.

The science of learning suggests that, in order for students to maximize their potential, schools not only need to provide kids with key foundations in math and literacy, but to foster motivation, agency, and critical thinking skills. Bridge’s tech-heavy model has clear advantages. But for complex skills, scripted learning is, as yet, untested. Critics contend that Bridge’s approach does not do enough to help children in the developing world leapfrog into an increasingly automated, globally connected society. Essentially, the question is whether a “better” education is good enough.

Quartz visited schools in Kenya, Nigeria, and Liberia and spoke to more than 40 people about Bridge, including former prime ministers, current and former education ministers, policy experts, employees, ex-employees and investors, as well as teachers, students, parents and academics. Our goal was to understand what is moving the needle on education in developing countries, and what role data can play in teaching and learning. We wanted to figure out whether the deep-rooted objections to Bridge are based on reality, or on idealistic notions about education.

We also wanted to understand the Silicon Valley ethos that drives Bridge. Because it uses technology to disrupt the delivery of a key service, it is often compared to Uber. And like Uber, at least under its founder Travis Kalanik, Bridge has little patience for its critics. Does Bridge represent an important breakthrough in scaling quality education? Or is it another Silicon Valley fad that’s driven by hubris, struggling to rightsize its ambition?

The Bridge business model

May and Kimmelman met at their five-year reunion at Harvard in 2004. That same year, Kimmelman sold Edusoft, an education software company, to Houghton Mifflin. Not long after, May witnessed the toll that a lack of proper education takes on a community while she was doing her doctoral work in anthropology in a village in northeast China. The couple married and together set out to build a global chain of low-cost private schools, using Kimmelman’s Silicon Valley contacts and experience building a company. They wanted to provide teachers with more structure and best practices, innovate around low-cost building design, and recruit beyond the traditional pools of teachers. Technology in classrooms came later. As tablets and smartphones became more affordable, they proved an effective way to distribute lesson plans.

They raised $100 million from big name tech giants like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg (via the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative), as well as global development organizations like the International Finance Company, part of the World Bank, and CDC, the UK government’s international investment arm. Investors were told the company could generate an internal rate of return, a measure of profitability, of 20%; an IPO would provide a potential exit.

The financial calculus was built on families paying on average $7 a month, or $84 a year per child (not including uniforms). It currently has 405 nursery and primary schools in Kenya, 63 in Uganda, 59 in Nigeria and four in India.

Liberia is different. There, Bridge is part of a high-profile experiment, started in 2016, to have outside managers run government schools in a public-private partnership; Bridge schools in the country are free to the public.

Bridge will need to keep expanding if it wants to become a sustainable business; it is currently losing about $12 million a year. The issue is a matter of scale: its low-cost model means it needs many more students to make money. There are 100,000 Bridge students today. At 500,000, May says it will break even. Its ambition is far loftier: to educate 10 million children by 2025, not just in basic reading and math skills, but through later primary years, when skills become more complex.

The Liberia experiment

When George Werner, Liberia’s education minister, asked Bridge to come help run some schools, Bridge leapt at the chance. After 14 years of civil war and a devastating outbreak of Ebola, Liberia had one of the worst education systems in the world. Only 38% of kids are enrolled in primary school (pdf); of the adult women who have finished primary school, only one-quarter can actually read a sentence.

“The status quo has failed,” Werner told Nick Kristof in the New York Times in 2017. “Teachers don’t show up, even though they’re paid by the government. There are no books. Training is very weak. School infrastructure is not safe. We have to do something radical.”

In 2016, the government did just that, launching a program called Partnership Schools for Liberia (PSL). It invited eight NGOs and for-profit companies, including Bridge, to run 93 government schools with 27,000 students. Under the partnership, all of the organizations would have to use Liberian government teachers. Students would pay nothing to attend the schools; only the management of the selected schools would be turned over to the operators. Meanwhile, the remaining government-run public schools would continue to operate as usual.

Edward T. Smith school in Gbelekpalia, run by YMCA (Jenny Anderson/Quartz)

Results after the first year suggest that the partnership schools are doing something right. The Center for Global Development’s recently released report showed that learning gains through the PSL program were significant. Students in partnership schools learned 60% more than kids in a control group of standard public schools. At Bridge, that figure was 100%: in other words, Bridge kids learned twice as much as those at public schools.

During a random spot check, teachers in PSL schools were 20 percentage points more likely to be present in school, and 16 percentage points more likely to be engaged in instruction during class time. Students in partnership schools spent twice as much time learning each week when taking into account reduced absenteeism, increased time working, and longer school days. Parents reported being happier. Overall, outsourcing education seemed to work. In 2017, Liberia expanded the program to a total of 194 schools, awarding Bridge the largest share.

The status quo

From a first-person perspective, it’s clear that Liberia’s PSL schools are a vast improvement over many government-run alternatives. Consider John Varfley, a government-run school located outside of Monrovia, Liberia’s capital. When I arrive at the dilapidated school in Montserrado County along the Kakata highway in November, two of the school’s six teachers are absent. “Fuck all” is written on the wall of one grade three classroom.

John F. Varfley Public School

Of the four classes I observe, one teacher seems engaged and able; the others do not. Counting and recitation constitute the extent of the learning activities afoot. “This is a struggling school,” admits Michael Topor, director for basic education at Liberia’s ministry of education.

The children have no books, and some don’t have a pencil. Rufus S. Gon-miah, the principal, is meant to take charge of the classrooms with absent teachers; he struggles to control the kids. He has them count from one to 50 over and over again, and when they veer off, he shouts at them to sit and behave.

According to Gon-miah, teachers make 9,000-15,000 Liberian dollars a month ($71-$119). They pay their own transport, which can eat up a lot of their salary. The school needs $500 to fix the hand pump on the well, where the school gets water, and another $30,000 for everything from doors to medicine.

“There are many problems,” he says: no textbooks, no doors, no medical supplies, and no food. What he needs more than anything? Money.

Bridge schools in action

The learning environment is quite different when I visit the Martha Tubman school in Salala, Bong County, three hours from Monrovia. I am greeted by a large team of Bridge employees—the principal and vice president for instruction, local academic officers, a public relations manager, and Sean O’Malley, Bridge’s head of academics for Liberia. Energy is high, positivity is constant, and order is visible. Kids tell me they love that “teachers are on our backs to learn.”

Martha Tubman school, operated by Bridge International Academies.

Bridge is scrupulous about gathering data on its tablets, recording everything from the precise time when a teacher arrives in school to the percentage of the scripted lesson that he or she completes. O’Malley takes copious notes as we visit various classrooms, all of which he says will go back to “Boston,” which coordinates with in-country teams on measuring learning and teacher performance.

In a grade two class, he notices that when the kids recite numbers, they add an “ee” on the end, so “six” sounds like “60,” and that one section runs one minute past the schedule. He mentions possible cuts to the lesson plan, and notes that the teacher is not calling on kids at random to ensure that everyone has an equal grasp of the material. Instead, the teacher is choosing students with their hands up. “He’s got to fight that urge,” O’Malley says.

Researchers in Cambridge and in-country curriculum officers can use that data to do A/B testing—to see if tweaking a lesson in one way on some classes produces better outcomes than a control group in another. In places often lacking basic reliable data, Bridge is building a system on unprecedented levels of information and accountability.

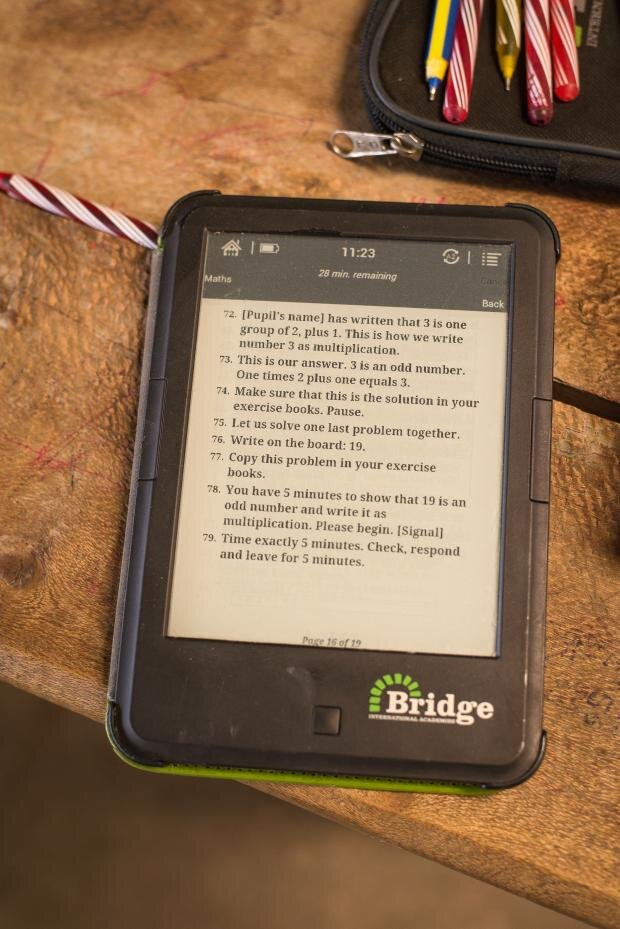

The most notable thing about a Bridge classroom, however, is the tablet, which teachers almost always seem to have in their hands. The teacher reads from tablets, including Kindle Nooks and other varieties, verbatim, offering instructions about when kids should open their books, close them, stand up, cheer, or work.

A tablet used by teachers at Bridge International Academy.

“You follow the guide 100%,” says Sampson Decee, principal of Martha Tubman. Bridge says that sticking to the guide is a very small part of how teachers are evaluated, but almost all the teachers Quartz interviews mention it first. A copy of one of Bridge’s teacher evaluations lists “Reads from the script 100% of the time while instructing.” (It’s number 14 on the image below.)

Part of a teacher evaluation at Bridge.

This approach solves many problems, according to Decee. “Before they would not teach the right lesson,” he said of teachers. He adds that before Liberia’s public-private partnership initiative, teachers had little to no monitoring or development, which meant that their weaknesses were unlikely to be corrected.

Bridge, by contrast, says it constantly assesses its teachers, starting with training before the school year begins. Throughout the year, teachers get feedback on how they are motivating students, how well the students behave, and how the kids are mastering the content. Bridge academic officers get reports from field officers who travel around the country and watch lessons, noting everything.

Bridge teachers’ fidelity to the scripts mean they have little agency. This is a vast improvement on an absent teacher, or an unprepared one. But it makes for a classroom that can be oddly lacking in human connection. When O’Malley and I leave the grade two classroom where he was taking notes, he mentions the teacher we have been watching is one of the best in the school. I am surprised. The teacher read the script well, and smiled often. But does that make a good teacher?

The heart of the debate

The issue of scripted lessons isn’t black and white, according to Luis Crouch, the chief technical officer for the international development group at RTI, a research-based nonprofit. Crouch helped develop widely-used assessment tools for early reading in developing countries. He says that scripting, which RTI uses, works well in some scenarios—and less well in others.

Kids need to develop a skill called automaticity—the ability to call up information automatically, like knowing that 4 + 4 equals 8, or knowing that Tuesday comes after Monday. Scripting works fine for helping students learn this kind of information. But Crouch worries that extreme scripting, in which teachers are required to follow a detailed script 100% of the time, could go too far.

“If it is too detailed and demands too much in fidelity to the script, it can’t lead to creativity on the part of the teacher,” Crouch said. He offered reading comprehension as an example. To develop and check for comprehension, “you need teachers who can converse with students in an open-ended way. By definition you cannot do that with scripting. It is mathematically impossible.”

“You need teachers who can converse with students in an open-ended way. By definition you cannot do that with scripting. It is mathematically impossible.”

A forthcoming RTI study of structured learning across 13 countries and 18 programs found that the best learning gains come from guides, but not from detailed scripts. “Having some structure for a teacher—a page per day—is showing really meaningful impact,” says Benjamin Piper, who works with RTI and heads up a research program in Kenya to test low-cost, scalable approaches to reading and mathematics. “Some programs, which write up every word teachers should say, our research is showing that is somewhat less effective than the less structured one.”

It’s clear that kids can learn important material with the scripted-lesson model. Femi Longe is the founder of Co-Creation Hub, a social innovation platform in Lagos, and much of his work has focused on improving how technology is used in schools. He applauds the fact that evidence shows students in Bridge schools make significant learning gains on measures of math and literacy.

But Longe worries that kids also need critical thinking skills that won’t come from scripted classes. “I don’t think someone who is reading from scripted text can teach critical thinking,” he says. “You can’t teach what you don’t have.”

Bridge, on the other hand, argues that the scripted lessons, which it calls teacher guides, don’t limit teachers—they empower them with the tools and guidance they need to succeed in the classroom. It assists them in creating dynamic learning environments, as opposed to the rote learning strategies used in many government schools. For example, Bridge says its classes are broken into fourths: one quarter of the time is spent activating prior knowledge; another quarter is the instructor teaching the kids material; the next emphasizes kids practicing what they’ve learned; and the last bit is used for summary and homework. “It lets you talk less” and engage students more, says Zeambo Davis, a Bridge teacher.

At work.

“We are a holistic school,” says May. “Structured pedagogy is not antithetical to that—it’s about helping teachers who themselves may not know these practices to ensure they have them.”

Whitney Tilson, a Bridge board member and investor who was a founding member of KIPP charter schools in the US, says the knee-jerk reaction that many people have against scripted lessons is because it violates our gut feelings about teaching. We think students learn best from inspired, creative teachers, and that scripted lessons shackle teachers, resulting in joyless, rote learning.

“This is a well-meaning but naive, elitist viewpoint, totally disconnected from reality, and evidence,” he writes in an email, “especially in countries like Kenya and Liberia.” (Tilson has not seen a live Bridge class).

“It’s always puzzled me,” he writes. “In a very poor country with poorly educated and trained teachers, if there’s a choice between a curriculum and lesson plans developed centrally by trained experts, carefully aligned with the national curriculum, and then delivered to teachers—versus letting every teacher develop their own lesson plans (or not!)—exactly what is the argument for the latter?”

May tells me that much of the criticism surrounding Bridge is invalid, based on fabrications or misconceptions about what the company’s schools are like.

“Most of the critics have never visited a school or actually spent an entire day watching teachers,” she says. “Many of the critics aren’t engaging in the true pedagogical discussion and aren’t interested in following the research question to see what helps children learn.”

Many people, however—including Bridge critics—are passionately engaged in precisely this kind of pedagogical discussion.

Learning is changing

Education reformers face two big problems today, explains Rebecca Winthrop, head of the Center for Universal Education at Brookings, in “Can we leapfrog? The potential of educational innovations to rapidly accelerate progress.”

First, there is the staggering inequality, with huge gaps between those who have access to high-quality education and those who do not. Bridge is tackling this problem head-on.

But an equally confounding problem is that we need to change what is taught and how it is taught. No child will thrive in 2017 with just the core competencies, such as math and reading. They also need to be able to solve problems, think critically, challenge assumptions, and create solutions. They need to be able to regulate their own emotions and work collaboratively. They need agency, or ownership over their own learning.

Winthrop notes there is an inherent paradox in these two goals. Schools that have most aggressively tried to close achievement gaps between rich and poor have often doubled down on traditional classrooms: teacher-led, compliance-based, and intensely focused on basic academic skills. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

“Learning sciences show that you can do both—core academic skills and higher-order thinking,” Winthrop says. “You can learn small things on the way to big if you set your learning goals to have kids develop a broad range of skills.”

Bridge is making significant gains closing math and literacy gaps, which are foundational and critical to every other piece of the puzzle. And Winthrop admires how Bridge continuously collects and uses data to shape their implementation. But she sees limits to their teaching model.

“If we truly want to leap forward in education, we need to move beyond traditional scripted lessons.”

The role of teachers

According to a 2017 World Bank report on global education, “Teachers are the most important factor affecting learning in schools.” It notes that “in developing countries, teacher quality can matter even more than in wealthier countries.”

John Hattie, a professor of education of the University of Melbourne, has examined more than 65,000 research papers (via 1,200 meta-analyses) on the effects of hundreds of different educational interventions. He discovered that things we think matter a lot—like class size or sorting kids by ability—don’t matter nearly as much as the quality of a teacher. “All of the 20 most powerful ways to improve school-time learning identified by the study depended on what a teacher did in the classroom,” is how the Economist summarized his findings.

Bridge teachers get feedback on how they teach. But it is unclear whether teachers will stay with a system that gives them so little freedom, especially when they have longer days and are paid less than they might earn at a government school (although they may be paid more reliably). Bridge declined to offer retention rates, saying turnover was low; the New York Times says high turnover in its early days led Bridge to institute two-year contracts to secure teachers’ commitment.

Some teachers say they like that the fact that Bridge does their lesson planning for them; others do not. Faith, the teacher at the Bridge school in Nairobi, says the scripted lessons are helpful—not limiting. “Even if I follow the teaching guide 100%, it makes me improve,” she says. “It tells you what to do, yes, but you also have to explain.”

Robin Horn, interim executive director of Ark’s Education Partnerships Group, which advised the Liberian government on the PSL project, has written that the scripted lessons can be conducive to building teachers’ skills. “It is clear that teachers use the scripts – and are required to do so by their supervisors,” he writes in an unpublished blog post after visiting some Bridge preschool classes while working for the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation in 2015. “But it is also true that teachers build teaching skills through the scripts, supervision, and weekly evaluations.”

Kids can ask questions when they want to, Bridge officials say. But Quartz’s visits to schools in Nigeria, Nairobi and Liberia found teachers sticking to scripts, which are tailored to each country’s national curriculum, with few students raising their hands to request more information or clarification. It does not seem that teachers are encouraged to veer off-script: their evaluations—a short one at least once a day, and a longer one each week—address how closely they follow the guide.

There’s also the issue of whether scripted lesson plans are, well, boring. Research shows that motivation is a crucial factor in successful learning; kids who see education as its own reward have a big advantage over time. Horn flags the issue in the same blog post. “There is one big problem that I saw that I am not sure if Bridge worries about because parents don’t: children did not seem to be enjoying school,” he writes.

“If you recite it, you don’t have to learn it.”

There is also little evidence about how well detailed guides work as kids move beyond basic literacy and numeracy. “There’s rigorous evidence on the impact of teachers’ guides in the early years, but there is limited research beyond grade three or four,” said Piper, from RTI. “I can’t think of any rigorous studies in developing countries.”

An alternative model

When you arrive in Moses Dagai’s classroom in rural Montserrado, about one-and-a-half hours outside of Monrovia, it is clear he is having fun. His grade-one children at Rising Academies’ Cecilia Dunbar school are taking a timed math quiz, with many smiling as the clock ticks and Dagai counts down, circling the room, peering over his students shoulders.

Moses Dagai at Rising Academies’ Cecilia Dunbar school.

The quizzes are part of a math curriculum called NUMBOTZ, created in the UK by Bruno Reddy, a math educator who tailored his UK curriculum for Liberia for free. It is meant to build math skills while also playing to kids’ competitive spirit: every week, one girl and one boy are selected to be Yottabot, the top math whiz.

Rising Academies, another of the PSL operators, was started in 2014 by British and Canadian entrepreneurs. It also uses teacher guides, but does not emphasize standardization to the degree that Bridge does.

Rising now runs eight schools in Sierra Leone and 29 schools in Liberia as part of the partnership program. In Sierra Leone, it charges fees of $14 to $15 a month; like Bridge, it is for-profit. According to the report on the results of the first year of the Liberian public-private partnership, students in Rising schools showed significant learning gains compared with regular public schools, and at significantly less cost than Bridge. (That said, Rising operated just five schools, versus Bridge’s 25, and the two had different agreements with the government.)

“The more detailed the scripting, the less risk the teacher will waver. But you lose something in the chemistry and human connection.”

All Rising teachers are provided a printed lesson plan every day. Dagai’s lesson plan sits on his desk during his lesson, and he refers to it occasionally throughout the period, for exercise ideas or a reminder of the goal for the day. But he does not carry it around with him, nor does he read from it out loud. The lesson plans are meant to be guides, not scripts. For the most part, I observe teachers being actively engaged, calling on students, working with small groups, or teaching a lesson.

“They are not as scripted as some organizations, and that’s a deliberate choice,” says Paul Skidmore, who co-founded Rising. “The more detailed the scripting, the more standardized the lesson will be, the less risk the teacher will waver. But the trade-off is you lose something in the chemistry and human connection that’s quite human and fundamental.”

Rising’s model is not built for scale. It is funded by internal investors, investments from development finance institutions, and the UBS Optimus Foundation, and aims to grow carefully. Skidmore says it will grow if quality can be sustained and cost effectiveness can lead to financial sustainability—something he poses as a question, and not a factual inevitability.

“Our growth will always depend on demand from families and consent from governments,” he said. “Both have to be earned; neither can be taken for granted.”

Rising is very forthcoming with the challenges it faces, and what the data from its experience in Liberia does and does not reveal. Skidmore said costs were too high in the first year, and worthy of debate and discussion. ”People are right to hold us to account for this.”

Before I leave the class, Dagai calls on a student to solve a math problem. The boy struggles. Other kids try to get the teacher’s attention, eager to answer. Dagai waits, and offers the child a prompt. The student is still stumped. Dagai asks other kids to offer help, revealing camaraderie in the classroom, and underscoring the fact that learning takes time. He makes sure it is still the boy who ultimately answers the question. When the child finally does, with ample help from the teacher and his classmates, both Dagai and the small boy look elated. The class cheers.

The evidence on Bridge

Bridge consistently points to exam evidence to make the case that its model is effective. For three years in a row, Bridge students in Kenyan Bridge schools outperformed the national average on the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE), an exam students take at the end of eighth grade. Ninety-three percent of Bridge graduates in Uganda completed the Primary Leavers Exam and scored in division one and two out of four, Bridge says. That compares to 56% nationally.

Academy Manager Shadrack Juma addresses his students at the Bridge International Academy – Kingston school in Nairobi, Kenya.

These results are impressive. But some critics suggest that they can largely be explained by the fact that Bridge kids come from families who have money to pay for school. “The evidence for learning gains disappears once you control for the socio-economic background of the children in Bridge schools,” says David Archer, a vocal critic of Bridge and director of ActionAid, a charity focusing on women and girls’ rights in 45 countries, citing evidence that the home environment is a key component to students’ success in education. Like others, he bristles at the idea of charging fees (pdf) to the world’s poor. Bridge says its typical Kenyan family earns $136.22 per month.

The randomized controlled trial in Liberia does show that Bridge can produce good results, if at a high cost, and with some favorable advantages. (It could only operate in schools with 2G cellular data access, schools that Sandefur argues were therefore closer to roads and better resourced.)

And yet Bridge seems to invite controversy everywhere it goes—for reasons that go beyond its educational methodology.

In 2016, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child raised concerns after the UK government awarded a £3.45 million grant to help Bridge expand in Nigeria, citing fears that low-cost private schools—which UNESCO says up to 25% of children in Africa attend—could impede the sustainable development goal of inclusive and equitable education for all by 2030. Last year, a group of 174 civil society organizations from 50 countries (pdf) banded together and called for international donors to drop their support of Bridge. (Bridge’s response to that letter is here.)

Among their concerns? By virtue of fees, Bridge excludes the poorest and most marginalized students in many of the countries where it operates. The letter also argues that Bridge has failed to conform to educational and legal standards in Kenya and Uganda, and cites concerns over Bridge’s lack of transparency. Bridge rebuts many of these points here, noting that much of the report was commissioned by Education International, a federation of more than 30 million teachers around the world, which Bridge says “openly campaign against education reform and are avid protectors of the status quo; the reliability of their assertions is fundamentally undermined by this starting premise.”

Meanwhile, for more than two years, Bridge has been mired in a legal battle about certification of some of its schools. In February 2017, a Kenyan high court in Busia County upheld a decision to close 10 of 12 schools (pdf) in the region for failing to employ enough trained and registered teachers and managers and inappropriate facilities. Bridge appealed the decision, and the Kenyan schools remain open. In Uganda, a High Court of Kampala also ruled that Bridge schools should be closed, citing concerns about unlicensed schools, unqualified teachers and an unapproved curriculum, as well as inadequate latrines. The schools remain open, following a subsequent high court ruling.

As a result of the uncertainty surrounding Bridge, Kenyan enrollment has fallen, from 100,000 in 2015 to 80,000 in 2017. Meanwhile, Bridge has been expanding elsewhere, backed by a grant from the UK’s Department for International Development and funds from CDC, its investment arm.

May testified before a parliamentary committee in 2017 about the UK’s investment in Bridge, and about Bridge in general. Committee members questioned May on why Bridge calls itself a “social enterprise” when it is structured to provide a return to investors; on why Bridge has “strained” relations with so many of the countries in which it operates; and why it was “hostile” to independent assessment. In response, May said that Bridge was founded with a social mission, and that relationships with governments had suffered from instances of “misinformation,” but had improved. She also said Bridge welcomed independent assessment.

After the inquiry, Stephen Twigg, chairman of the UK parliament’s international development committee, wrote in a letter to the (now former) minister for international development, “The evidence received during this inquiry raises serious questions about Bridge’s relationships with governments, transparency and sustainability.” (The full report of the committee is here; Bridge pointed me to a section which calls its model “innovative, scaleable and impressive.” The Bridge response is here.)

Tilson, the Bridge investor and board member, says the pushback against Bridge is part of a campaign by teachers’ unions to shut the company down, since it does not always use certified teachers. Education International has waged a fierce campaign against Bridge. “What we are most concerned about is their business model, which is predicated on unqualified staff delivering a highly-scripted curriculum in facilities that are not satisfactory,” said Angelo Gavrielatos, project director for the global teachers union. They want governments to do more to provide better public education.

May says Bridge wants governments to invest in more public education, too. “I hope you noted, I didn’t say we believe in private schools. We don’t. We believe in good schools for all children and that all children can learn. And if one day there are truly great and truly free schools, Bridge wouldn’t be operating affordable private schools.”

The results in Liberia

Despite Bridge’s investment in data collection and assessment for its own schools, critics say it has historically been resistant to assessments from outsiders.

In Liberia, the government wanted to have an independent evaluation of the PSL to see if it worked, and if public schools could learn from innovations the operators brought; Bridge resisted the prospect. “Bridge actively opposed the [assessment] at the beginning of year one because they thought it would be too difficult to demonstrate impact in the first year,” says Sandefur, one of the lead authors of the independent report assessing the PSL’s impact. Bridge says that its concerns were over the short notice, and because the intensive assessment meant that it would need to operate at fewer schools, depriving kids of the benefit of the program. Bridge was overruled.

The report showed that strongest learning gains clustered around four operators, including Bridge. One operator—Street Child, an international NGO—spent $48 to produce roughly similar results, compared to $663 for Bridge in its first year. (Bridge notes that this includes both set-up and operational costs, while the others are solely operational costs.) “The [Bridge] program needs to get considerably cheaper, and a cheaper version of the program hasn’t been tested,” Sandefur said. “It’s worth piloting and testing a version of the program under real-world budget constraints.”

Steve Cantrell, Bridge’s head of measurement and evaluation, attributed the high figure to start-up costs, and said that costs will come down as Bridge scales. Bridge estimates costs for 2017-18 will be $220 per child, and says that the figure will come down to $50 per child by 2020.

Another key criticism: Bridge chose not to use more than 50% of the teachers it was given in Liberia, saying that many were illiterate and couldn’t read the lesson plans. Those teachers reverted to the country’s education ministry, which then decided whether to reassign them to other schools. That complicates the idea of a public-private partnership, in which operators are meant to work within the existing system. “If these are the worst teachers and they are out of your school but in a school nearby, are you bringing up your quality at the cost of the other public schools?” asked Horn from Ark. If so, that is not a fair outcome for students, and does not improve the system.

Other operators chose to try and train teachers who had promise, but lacked skills. Rising mostly trained the teachers it had, rather than trade them for better-qualified ones. “We decided to build capacity. They have the passion,” said Caroline Veh, a 15-year veteran teacher and educational officer at YMCA, the local Liberian NGO which also manages PSL schools. Bridge also enforced caps on class size of 55 children per class, per its contract, according to the Center for Global Development report, which many other providers did not.

The future of education

Kolleh B Livingston, a 71-year-old retired judge, is the head of the PTA at Martha Tubman, the Bridge school in Salala, Bong County. He has 10 children, including a third-grader in the school. He is elated by the arrival of Bridge. “I see great improvement. I see time and care.” Some students didn’t know how to write before, he says. Now? “My third grader is writing better than a tenth grader.” Where the government school had chaos and apathy, Bridge has order and procedures, positivity baked into its scripts, and an emphasis on building character. Other parents echoed this sentiment.

Bridge has impacted the education ecosystem in every country in which it operates, and others beyond it. Its supporters are right to celebrate the data-driven approach which produces evidence to build better education systems, as well as ways to improve feedback for teachers. For-profit ventures should be able to operate and offer alternatives where there are none—though they must be properly regulated—and Bridge has shown how to build accountability around teachers, if not autonomy for them.

Bridge Academy students practice mathematics at the Kingston school in Nairobi, Kenya.

But it’s worth listening to Bridge’s critics as well. In Liberia, schools in the public-private partnership program were assigned 37% more teachers, including first pick of the best trained ones, and spent a lot of money. Double—or in Bridges’ case, increase by six-fold—the expenditure on education in any country, and you usually get better results.

Rising and Bridge each show that innovative models can improve education in developing countries. Students in both classrooms appeared engaged, and the teachers were prepared. The biggest difference was not just in the matter of guides versus scripts, but in the level of humility and curiosity with which each organization seem to approach its role in the educational ecosystem. Rising asks questions and invites feedback; Bridge seems certain it has the answers.

If Bridge wants to operate at scale, and pursue more public-private partnerships, it seems incumbent upon it to show not only independent evidence that it can produce learning gains, but also that it can do that at a reasonable cost.

Of the nearly 40 people I spoke to about Bridge, everyone who was not an employee or investor in Bridge said that the company had an inherently confrontational culture. Bridge bristles at questions that other organizations seem happy to answer, from evidence on scripting to how it characterizes its tablets (guides, not scripts). The tone of its answers ranges from combative to patronizing. And at times, their responses seem misleading. It insisted that it did not ask for the same funding the other operators got from the Liberian government, but multiple sources told Quartz it tried hard to do just that. (Bridge apologized for the error.)

It’s hard to tell how much of the controversy surrounding Bridge arises from entrenched players feeling threatened (which they clearly do), and how much stems from Bridge being single-minded about its mission to the detriment of its own cause—a familiar malady in Silicon Valley. Part of the conflict is the model itself: To scale, it needs a highly replicable approach like scripted learning. But automating such a large part of teaching is necessarily fraught.

Some argue that Bridge is simply being punished for being a first mover in an institutionally conservative space. “I have an affinity for Bridge and I will scream that from the mountaintop,” said Gbovadeh Gbilia, head of the education delivery unit, set up to continue the implementation of the education ministry’s reforms with the new administration (Liberia just elected a new president). ”When you want to do something first—an innovation, something disruptive—and you are the first entry, you get the biggest hit.”

I ask May why Bridge seems to generate so much controversy, and whether she thinks the company has made any mistakes along the way. She says that Bridge is focused on dealing with the hard realities of families living in poverty, and it simply didn’t foresee that they needed to work with the global development community. “We realize the extent to which it is important to engage with the development community, and to have them understand your work rather than create fables about it. But that’s a pretty big expense,” she says.

She does not entertain the possibility that someone might just disagree with the Bridge mission of heavily-scripted, for-profit education for poor children. “We think it’s important that people make data-driven decisions and leave their ideology outside the classroom,” she says. And yet, Bridge itself is fueled by its own ideology, as surely as any other organization trying to solve the problem of education in developing countries.

Sometimes the din of debate drowns out the scope of the problem: 263 million kids aren’t getting an education. ”Education cannot wait,” says Gbila. When there is a crisis and an un-ideal situation–conflict, migration, a pandemic–what do you do to make sure the child continues to learn in in that risky environment? You take action.”

And yet sometimes the mission can muddy the goal. In every educational program I saw in Liberia, schools had no food for children. At Martha Tubman, the children had access to a bucket of water and a cup they all shared, but no food. At Rising, YMCA, and John Varfley, the public school, the situation was the same.

The UN’s World Food Program sometimes offers food to public schools in Liberia, but did not for the partnership schools—many of which were spending a lot to make classrooms functional and learning possible. Minister Werner has raised the importance of the issues, but it remains unsolved.

The lack of food came up everywhere I went. “The children are hungry, they cannot learn when they are hungry,” says one father siting on a bench beneath a bougainvillea tree near his child’s school. Many operators in Liberia succeeded in getting kids to school, and keeping them in their seats and learning. But few chose to feed them. It seems a data point worth studying.

Lily Kuo in Nairobi and Yomi Kazeem in Lagos contributed additional reporting to this story.

Correction: Street Child spent $48, not $41 per child, as a previous version of the article stated. It is an international NGO, not a local provider.